Earlier this year, in a momentous and combined decision, the UK Supreme Court and Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) reset the extended form of “joint enterprise” liability in England & Wales and Jamaica.

There were audible gasps (at 7 mins 40) in court as Lord Neuberger announced the judgment. Much has already been said by expert practitioners and academics about the significance of this decision. This post makes just a few short observations on what is surely one of the most significant criminal law judgments in years.

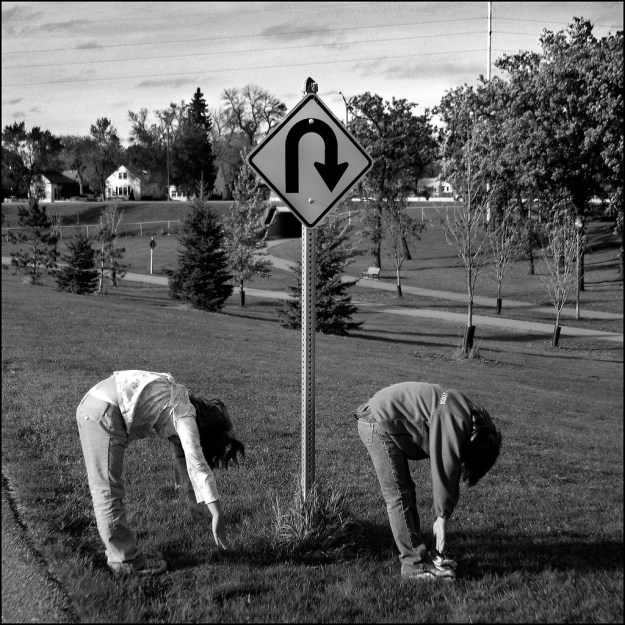

A joint enterprise U-turn (Credit: gfpeck under Creative Commons)

The two cases were Jogee (an English appeal) and Ruddock (a Jamaican appeal). Both appellants had been convicted of murder. Although neither had stabbed the victim, each was found guilty of murder following directions given by a judge on joint enterprise liability.

Joint enterprise is not a legal term of art

Following an extensive review of the authorities (and persuasive unpicking of the caselaw from the counsel involved), the unanimous panel of five Justices (Lords Hughes and Toulson, with whom Lord Neuberger, Lady Hale and Lord Thomas agreed) held that the common law took a “wrong turn” in 1984 when the JCPC held that a person who participated in a joint venture with mere foresight of the possibility of murder or serious harm would, if death resulted by the actions of another, be convicted of murder: Chan Wing-Siu v The Queen [1985] AC 168.

That wrong turn took place in London. But it originated in Hong Kong, from where appeals then lay to the JCPC. This “extended” form of joint enterprise (sometimes called “parasitic accessory liability”) was followed many times after 1984. In many jurisdictions.

The judgment in Jogee/Ruddock disparages “so called ‘joint enterprise’ liability” (para. 61). It clarifies that joint enterprise is not a “legal term of art” (para. 77) because it is too vague: it can refer to a variety of situations; both principals and accessories. The court held that the proper mens rea test for accomplice liability is whether a secondary party intended to assist the principal to commit the crime. The alleged accessory’s foresight of what the principal might do is relevant to deciding the secondary party’s intent. But it was wrong to treat it as being decisive. It is “illegitimate” to treat foresight as an “inevitable yardstick of common purpose” (para. 87).

Time to discard illegitimate yardsticks (Credit: Lynn Friedman under Creative Commons)

The implications of this decision

Much attention will rightly be given to the impact of this judgment on persons convicted of murders committed by others. But the case has broader implications. The judgment contains important nods to this.

The principles for criminal law are the same whether it is a forged cheque or a deadly stabbing. In the words of Lord Neuberger when summarising the decision: “sometimes [it] is murder, but the rules are the same whatever it is.” The judgment resets criminal law to more coherent underlying principles of accessory liability.

Of further interest, the judgment states that there can be cases of intentional assistance or encouragement to commit an offence,

without [the secondary party] having a positive intent that the particular offence will be committed. That may be so, for example, where at the time that encouragement is given it remains uncertain what [the principal] might do; an arms supplier might be such a case. (para. 10)

The underlying question to be determined is whether, in all the circumstances, the accomplice intended to assist the principal to commit the offence? And here the generic reference to “offence” again highlights that this decision is not just about murder.

The emphasis on intention to assist an offence involves a higher standard than mere knowledge of possible consequences. In summarising the law on accessory liability, the judgment cites two well-known cases (National Coal Board v Gamble [1959] 1 QB 11 and Gillick v West Norfolkand Wisbech Area Health Authority [1986] AC 112) without exploring the differences between them. (Gillick has rightly been described as an “outlier” on accessory liability (see the discussion in P. Davies, Accessory Liability (2015: Hart Publishing, Oxford), at p. 76). The point here is that uncertainty might still exist over what must be shown to demonstrate that an accessory intended to assist the offence. It will all depend on the particular circumstances.

That aside, it is worth returning to the jurisprudential significance of Jogee/Ruddock and its abolition of the extended form of joint enterprise. As far as I know, this is the first time that the UK Supreme Court (or House of Lords) combined an appeal with the JCPC.[1] The combination avoided the awkward situation that arose following AG for Jersey v Holley [2005] 2 AC 580, when a panel of nine sitting in the JCPC rejected the English law on provocation as set out in R v Smith (Morgan) [2001] 1 AC 146. This generated difficult questions over whether lower courts in England should follow the House of Lords or the JCPC. Ultimately, the Court of Appeal (sitting as five judges) opted for the JCPC’s approach. And leave to appeal was refused: see R v James [2006] EWCA Crim 14.

It is also of note that the Supreme Court / JCPC felt able to reverse more than 30 years of caselaw without sitting as an enlarged panel of seven or nine. Maybe the quality of the appellants’ arguments and the decisiveness of the decision trumped any need for an enlarged panel?

The reset of joint enterprise will have a profound impact on the common law: beyond the law of murder and probably beyond England and Jamaica. It remains the case that an accessory who intends to assist a crime is as guilty as the principal. But the inference of intention is no longer so automatic. It must be scrutinised based on the particular facts of each case.

(For a discussion of joint liability in tort, as opposed to criminal law, see my post here.)

[1] The JCPC has previously combined appeals from various jurisdictions, including when a panel of nine reviewed the constitutionality of the mandatory death penalty in a trilogy of cases from Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados and Jamaica: Matthew v State of Trinidad and Tobago [2005] 1 AC 433; Boyce and another v The Queen [2005] 1 AC 400; and Watson v The Queen (Attorney General of Jamaica intervening) [2005] 1 AC 472. The JCPC held that, whereas the mandatory death penalty was unconstitutional in Jamaica, it conformed with the constitutions of Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados. The unhappy distinction arose because of different “savings clauses” within certain (independence) constitutions which excluded or limited challenges to a law in place at the time of independence. Jamaica had amended its law after independence with the result that it was not saved from challenge, whereas the original laws in Trinidad and Barbados survived (albeit criticised for being “cruel and unusual”).

One thought on “Jogee/Ruddock and joint enterprise”